Ferris – UC Berkeley Psychedelic Journalism Fellow Tiney Ricciardi explores the importance of youth drug education as psychedelics go mainstream.

What is psychedelic journalism?

In this series, I interview psychedelic journalists and writers from across the globe. Each conversation reflects a fragment of the kaleidoscopic world of psychedelic science and culture. Subscribe to my newsletter to get your free weekly dose of psychedelic journalism.

It all started with beer.

“That’s a mind-altering substance,” says psychedelic journalist Tiney Ricciardi.

A devout craft beer drinker, certified beer judge and host of the Grapes and Grain podcast, Tiney reported for the Dallas Morning News for seven years with a focus on ‘obsessions’, rather than traditional beats. This allowed her to dive deeper into one specialism, peering through beer goggles at the emerging craft brewery scene.

“In 2012, I could count the number of craft breweries on one hand,” says Tiney, who became the newspaper’s first dedicated beer editor. “But by the time I left, I had a spreadsheet with over 100 different craft breweries.

“A lot of legislation came out of this — trying to keep up with these new beer makers. Tap rooms weren’t legal for a long time. All of that changed during my tenure.”

Tiney did not consider writing about psychedelics until she moved to Colorado to join the Denver Post in January 2020.

“In Texas and Dallas specifically, it was very taboo.”

Her new beat covered “vices” including the newly legalised cannabis and sports betting industries.

“When I moved to Denver, it was a real culture shock,” she says. “Before, I couldn't talk openly about [drugs] for fear that I could get in trouble or get arrested. I had to learn how to speak openly about cannabis use.”

Tiney has used drugs like cannabis recreationally since she was 15 years old.

“When I was a kid, I was in the music scene and experimenting with ecstasy, LSD and shrooms,” Tiney says. “I love music festivals and being able to go out and be in nature. [Psychedelics] are just a really great enhancement for that.”

But today, despite reporting on the blossoming psychedelic space, Tiney prefers to stay lucid.

“I don’t like to trip out that much,” she says. “A gram of psilocybin tea once a year is plenty for me. But having those experiences when I was young gives me more insight to write about the subject.”

Now her reporting has evolved to cover what she calls “earthly delights” — beer, cannabis, psilocybin, restaurants, reality TV, the great outdoors.

“What I report on is very aligned with my personal interests.”

Tiney’s first psychedelic reportage was a story about Rabbi Ben Gorelick, the founder of a multifaith community called The Sacred Tribe, which promotes the use of psilocybin mushrooms as part of a spiritual practice rooted in the Jewish mystical tradition, Kabbalah.

For the feature, Tiney attended a ceremony where people convened to ingest the “sacrament” and participate in holotropic breathing exercises.

“That was one of the trippiest experiences I’ve ever been through,” she says. “I was a fly on the wall. I did not consume psilocybin. But I partook in the breathwork ceremony.

“Halfway through I had to go sit on a chair because I was hearing people moaning, crying, screaming.

“That was an interesting, immersive experience. I don't think I could have told the story without being there.”

Tiney’s investigative piece explored the cultural, clinical and legal contexts that allowed the rabbi to operate, including the different city, state and federal laws on psychedelics and what constitutes “religious use” of entheogens according to the Religious Freedom and Restoration Act 1993.

Denver became the first city to decriminalise personal possession and consumption of psilocybin in 2019, inspiring similar initiatives in Oakland, California and Washington, D.C.

“Decriminalise is kind of a funny word here — because it doesn’t mean there are no criminal penalties,” Tiney says. “It just made enforcing those penalties the lowest priority for local law enforcement.

“Technically, you could still be arrested, but if you were it was often because there were other circumstances surrounding it or other drugs involved.”

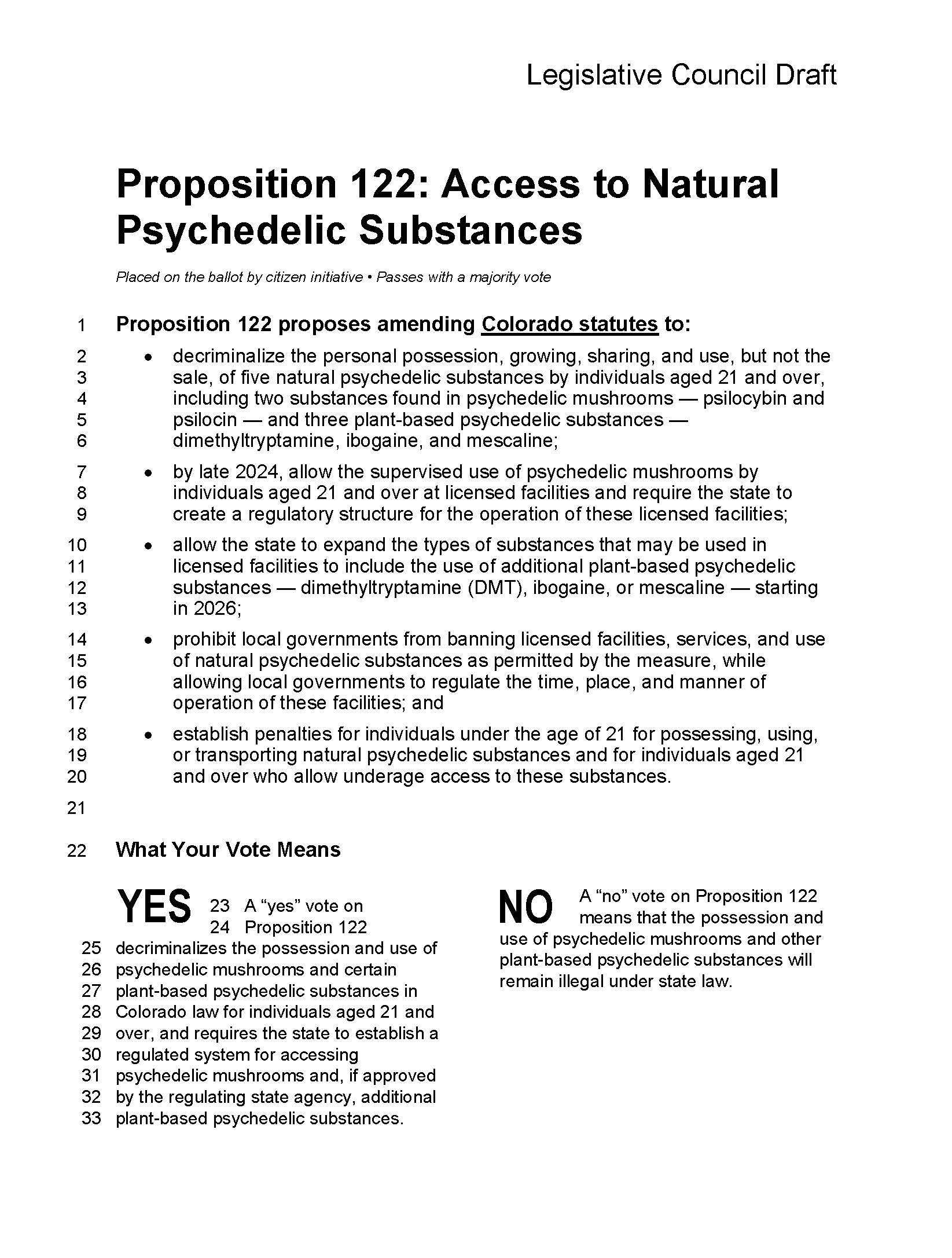

Rabbi Gorelick was arrested but did not face prosecution after Coloradans voted to pass Proposition 122 in November 2022, which legalised personal use, possession, growth and transport of psilocybin and other related substances for adults over 21 in Colorado.

“It is, however, a crime to sell it,” Tiney says. “So you can see how the legal framework is a little grey and all over the place.

“In general, there is momentum in the United States towards unravelling the criminal aspects around psychedelics and integrating them into our society in a medicinal way — and in a way that keeps people out of jail.”

Under Proposition 122, regulators could also legalise mescaline, ibogaine and DMT to be administered in medical settings by 2026.

“That set the stage for cultural acceptance here of experimenting with psychedelics and making it part of the mainstream lexicon,” Tiney says.

“These substances can have positive effects on mental wellbeing — whether it's for terminally-ill cancer patients or with regard to addiction and treatment-resistant depression.

“But they’re not a magic pill by any means,” Tiney warns. “Sometimes the marketing makes it seem like all you have to do is shrooms and then you'll be fine. There's still a lot of education to be done on that front.”

Now, when Tiney interviews those who advocate for drug prohibition, she asks whether her subject has ever tried cannabis or psilocybin.

“Nine times out of ten — actually I would say 100% of the time I’ve asked that question — the answer is ‘no’.

“If you don't have experience with something, it's natural to be scared, right? But there's a lot of self-exploration to be had.”

Tiney cited a 2020 study from Unlimited Sciences and Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research, which surveyed the contexts in which psilocybin users take the drug.

The largest percentage of respondents (40%) said “self-exploration” was the primary reason for undergoing a psychedelic experience, followed by those experimenting with psilocybin for their “mental health” (30%) and for “therapy” (10%).

“I never learned about these substances except through my own personal experiences,” Tiney says. “And while I think that was valuable, in our current world I think it can be dangerous.

“There are several other life paths I could have gone down because of my experimentation. In that respect, I’m lucky or I just had a really great network and environment that I was testing in. But a lot of kids don't have that.

“I don't necessarily think that experimenting with drugs is inherently a bad thing. But that's where my interest for this fellowship piece comes from.”

This year, Tiney was awarded the Ferris – UC Berkeley Psychedelic Journalism Fellowship. She developed her proposal with Ann Marie Awad, creator and host of the drug policy podcast On Something, who was also awarded the psychedelic journalism fellowship in 2022.

Tiney will use the $10,000 grant to write a piece on how departments of education, regulators and legislators can improve drug education and empower youth as psychedelics enter the cultural mainstream.

“I will explore how — if at all — it has evolved as drugs have become more normalised and more legalised as we are ramping up to a legal psilocybin industry here in Colorado.”

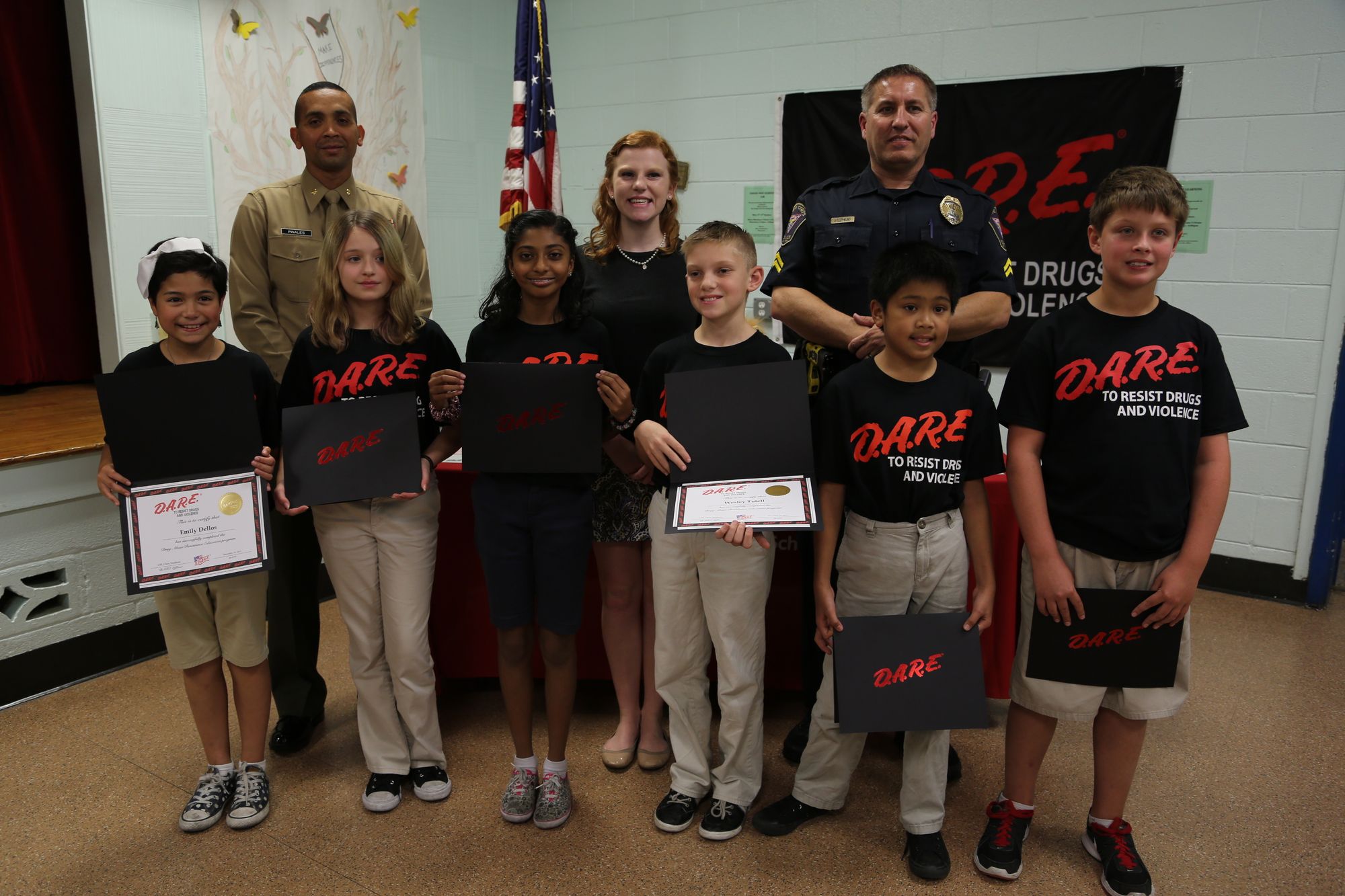

One of the most widely known drug education programmes for young people in the U.S. is called Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E.). It was most prominent in the late 1990s and early 2000s, though it is still active today and involves schools and local police enforcement collaborating to prevent the use of illegal drugs, membership in gangs and drug-related violence.

“I grew up in the D.A.R.E. era,” Tiney says. “Cops would go into schools and basically teach kids about drugs. But from a mindset of: ‘These [drugs] are illegal, these [drugs] are bad, don’t do drugs.’

“It’s basically like drugs are the boogeyman.”

But Tiney argues that the current drug education programme is not fit for purpose.

“It’s been proven time and time again that D.A.R.E. does not work,” Tiney says. “They are not providing actual education: what drugs are, what their effects are, what their potential risks are.

“There’s value in knowing how to do them safely, even if it’s just for recreational purposes. And as we know from things like sex education, just saying ‘don't do it’ is not going to keep kids from doing it.

“It couldn't be more timely because our country is experiencing a Fentanyl crisis. Teenage overdoses are at an all-time high because of this black market drug.”

Tiney also plans to build a survey which will measure how young people in Colorado are educated on drugs compared to other states with different politics, such as Alabama or Mississippi, for example.

“But I think the most important part of my reporting is going to be getting in front of students and asking them: What do you know about these substances? Where did you learn that? What else do you want to know?”

Tiney hopes that the piece, which is expected to be published later this year, will have even more impact by being repurposed for platforms which are more popular with Gen Z like Instagram or TikTok, rather than legacy media.

“It’s a huge honour to be able to add this to my résumé and say I’ve got the backing of Tim Ferriss, Michael Pollan and UC Berkeley,” Tiney says. “Hopefully, it is something that will serve me as I go forward in my career.

“Colorado has an opportunity to lay the foundation and shape the future as we unravel this really harmful War on Drugs. Hopefully, it could have a monumental effect.”

Despite the potential medical health benefits of psychedelic-assisted therapy for young people, the movement for progressive policy reform and drug education will still need to win over conservative voices.

“When people are against undoing the War on Drugs and removing criminal penalties, it’s always: ‘What about the kids?’

“If the argument against legalisation is ‘what about the kids?’, then what are we doing about the kids?

“As we prepare to legalise psilocybin and psilocin — and potentially other drugs in the future — it is imperative that we’re empowering the next generation to make the best of this.”

Tiney Ricciardi is a journalist with the Denver Post based in Colorado. You can follow Tiney’s work on her website, Twitter and Instagram. Her psychedelic journalism article on youth drug education will be published by the Denver Post in 2023.