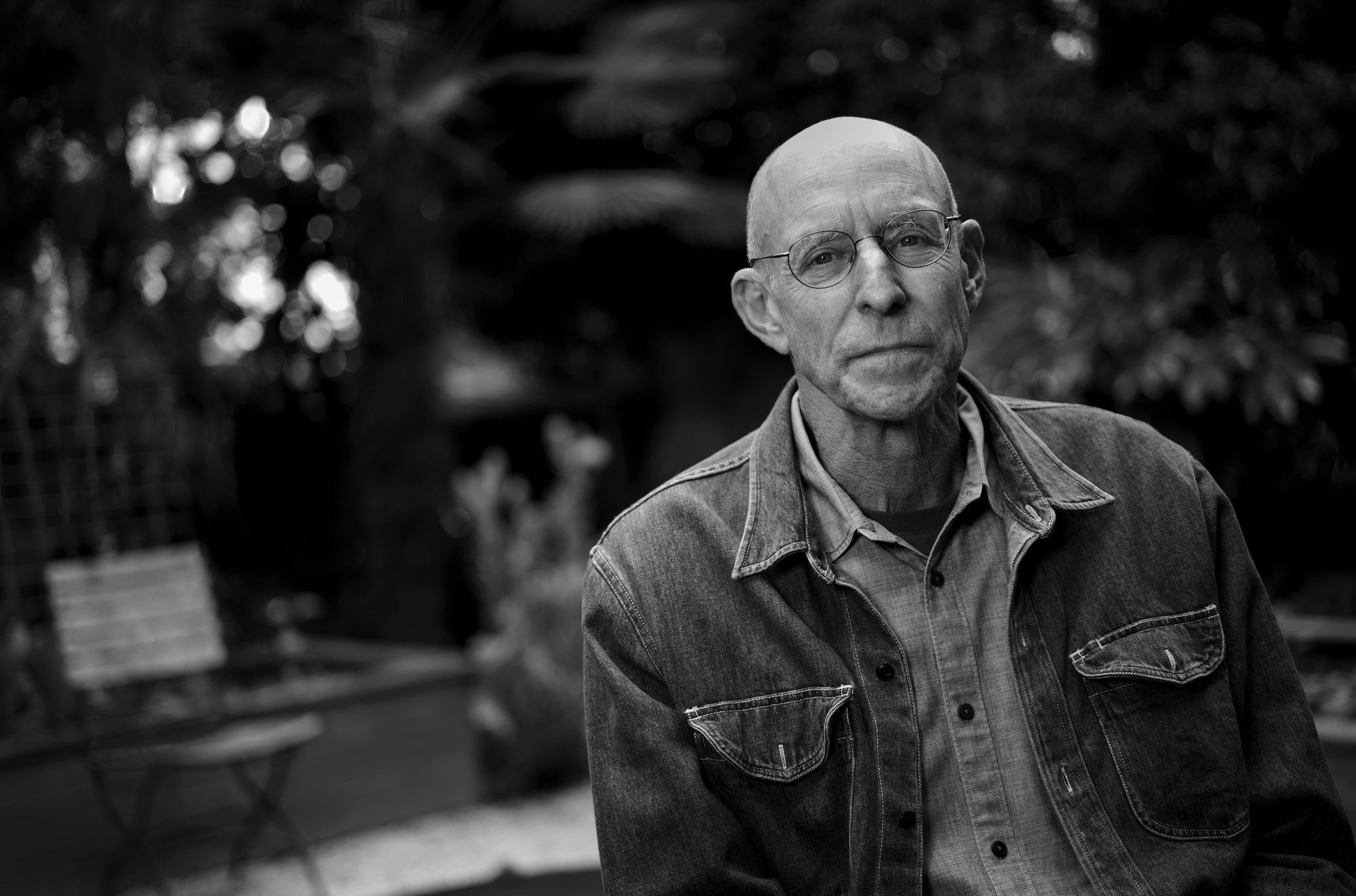

Ferris – UC Berkeley Psychedelic Journalism Fellow Meryl Davids Landau says the scientific evidence must take priority as the hype surrounding psychedelic-assisted therapy grows.

What is psychedelic journalism?

In this series, I interview psychedelic journalists and writers from across the globe. Each conversation reflects a fragment of the kaleidoscopic world of psychedelic science and culture. Subscribe to my newsletter to get your free weekly dose of psychedelic journalism.

Meryl Davids Landau is a science, health and climate journalist based in Florida. She has published articles in the New York Times, National Geographic, Vice, Reader’s Digest and more.

Meryl also publishes women's fiction about mindfulness and her novel Warrior Won earned an Independent Publisher Book Award (IPPY). Her narratives explore how protagonists maintain inner peace in the face of adversity.

But Meryl did not consider writing about psychedelics until she received a call from an editor at Good Housekeeping. She was commissioned to write a feature about how illegal drugs like LSD, magic mushrooms and MDMA are being studied to treat addiction, depression, anxiety and eating disorders.

“I thought: Wow — mainstream American women are going to be reading about this! If Good Housekeeping is interested [in psychedelics], this is something I need to be paying attention to as a health journalist.”

Meryl discovered that psychedelic journalism aligned with her interest in consciousness and holistic health. Interviewing those that had undergone psychedelic-assisted therapy, she saw parallels between the transformative experiences catalysed by these alternative medicines and those generated by spiritual and meditative practices.

“It’s not just about the one experience and how amazing it is — but does it transform your life?

“They’ve got a new perspective on themselves and the world,” Meryl said. “They feel like they’re connected to something greater than themselves.

“I think meditation does the same thing. It obviously takes a lot more discipline. But psychedelics powerfully do this as well.”

In 2022, Meryl attended the psychedelic business conference Wonderland Miami. During a panel discussion, the speaker asked how many attendees had microdosed psychedelics like psilocybin or LSD.

“The number of hands that went up in this room was kind of startling to me. The vast majority of people were microdosing.”

Meryl concedes that an informal survey conducted at a psychedelic conference would not be representative of national attitudes towards microdosing. Still, this incident affected her enough to write a piece investigating whether taking a sub-perceptual amount of a psychedelic could have mental health benefits.

Meryl’s reporting interrogates the strengths and shortcomings of the current healthcare system.

“Western medicine — a drug or surgery — is very helpful for certain conditions,” she said. “If I’m in a car accident, I’m not going to an acupuncturist.”

But Western medicine can be ineffective in helping those suffering with chronic conditions, such as treatment-resistant depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

“Partly that’s where the clamouring for psychedelic drugs comes in — because mental health care is so woefully inadequate at the moment, and a lot of people have a need for something different.”

Her articles on ketamine therapy and telehealth for MindSite News and training programmes for psychedelic therapists for National Geographic explore the importance of preparing the correct infrastructure and support network as psychedelic-assisted therapy gains momentum.

“Who is the person you're with when you do this very vulnerable thing and who is helping you to unpack all of that? It's really crucial.

“If in the middle of the night you are hit with a profound insight that destabilises you — what are you going to do about that?

“Whether it’s meditation or psychedelics, it's really good to do it within some kind of structure or paradigm, where there are resources or people that can help guide you.”

But this is not Meryl’s only concern about the nascent psychedelic industry.

“I think the hype is starting to get ahead of the science,” Meryl said.

“Psychedelic therapy could be a real game-changer for mental health and other things, but I think journalists have to be really careful.”

Meryl highlights how wellness spas in the US are advertising sublingual ketamine in off-label treatments for psychiatric disorders beyond its approved use by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as an anaesthetic.

“Ketamine clinics, in my opinion, are overhyping the benefits of ketamine,” Meryl said.

“There hasn’t been a lot of research on ketamine outside of its FDA indication as an anaesthetic for surgery. That’s what it was approved for in the US. Once a drug is approved, it can be used legally for other things.”

Ketamine modalities such as tablets, lozenges or infusions are not approved for treating any psychiatric condition.

In an article for Missouri Medicine, Robert Sobule and Muaid Ithman wrote: “Unsupervised ketamine treatment is dangerous, debatable, and extremely worrying.”

Esketamine, a chemical variant of ketamine, is the only FDA approved form of ketamine for treatment of depression and suicidality.

“Small studies show it’s helping with severe depression, but then what happens with a lot of these drugs is that they start to be marketed and used outside of those indications,” Meryl said.

“Journalists bear a responsibility to make sure that we are not part of that problem.”

Meryl would also like to see larger study samples with hundreds of participants from diverse backgrounds and long-term follow-ups to ensure the robustness of psychedelic research before these drugs are legalised.

One example of how this has been done successfully is the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) trials using MDMA to treat PTSD. Nature Medicine published the results of the second MAPS-sponsored Phase 3 trial of MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD in a large, diverse cohort on 14 September 2023, confirming prior positive results.

MAPS Founder and President Rick Doblin said: "Thanks to the combined efforts of dozens of therapists, hundreds of participants who volunteered in MAPS-sponsored trials, and many thousands of generous donors, MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD is on track to be considered for approval by the FDA in 2024.

"We hope that MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD will be approved by the FDA next year — and that our Open Science, Open Books principle will inspire researchers to make this just the first of many psychedelic-assisted therapies to be validated through diligent research."

Even with more robust studies, Meryl says we must not be overzealous when interpreting the results.

“The only statement that can be made from the MAPS research is that MDMA seems to be effective over the long term for people with PTSD. The research is showing something very specific in a very specific population.”

It is therefore premature to assume MDMA can be used to treat conditions such as treatment-resistant depression or anxiety.

Further problems arise surrounding the price of treatment and accessibility.

“We have to be aware of the cost factor. If it does prove to be as effective as it seems, who is going to be able to afford it?”

This year, Meryl was awarded the Ferris – UC Berkeley Psychedelic Journalism Fellowship. She is using the $10,000 grant to research and compose a feature about psilocybin and end-of-life.

Through her reporting, Meryl has heard firsthand about both the revelatory and the challenging aspects of the psychedelic experience.

In her Good Housekeeping piece, Meryl told the story of Ellen Cox, a general manager at a brewery in Washington, D.C., who quit smoking after a single psilocybin session.

“That really brings home the potential power of this kind of therapy,” Meryl said. “But during her trip, there were some good things and some challenging moments. That makes me conscious as I'm writing that I need to make sure I don't paint this overly rosy picture.”

She also tells the story of Renee St.Clair, a San Diego attorney in her fifties who suffered from major depression most of her adult life. After an intravenous ketamine infusion, Renee was gripped by a sinister hallucination in which she feared that her brain, which was floating across the room, might never return to her body. Despite this troubling experience, she continued the treatment and credited ketamine with alleviating her constant thoughts of suicide.

Meryl emphasises the responsibility that journalists, while reporting on the potential therapeutic breakthroughs made possible by psychedelic medicines, must also caution the public about long-term or rare side effects, as well as being transparent about the unknowns.

“I love interviewing people to humanise health stories. Otherwise it’s just stats and a dry recitation of facts. People's experiences bring it to life. But that’s also where I get a lot of the caveats.”

Ultimately, Meryl’s writing attempts to uncover the best, evidence-based methods for wellness.

“For me, meditation was a transformative experience. When I started feeling like I was connected to something larger than myself — that can really change your whole life.

“What is the purpose of doing a psychedelic? It is to try to learn how to have more equanimity and positivity — and to rid the mind of mental illnesses that limit that.

“My hope is that psychedelic medicine can eventually do that for people who could really benefit. So, if these medicines ultimately prove they can help people get that, I'm in favour."

Meryl Davids Landau is a freelance journalist based in Florida. You can follow Meryl’s work on her website and X (formerly Twitter) and you can buy her books on Amazon. Her psychedelic journalism article about psilocybin will be published in late 2023 or early 2024.