Welcome to Afterglow, a newsletter that will change your mind. My name is Charles Bliss and I'm a psychedelic journalist from Norwich, UK.

This week we're nullifying our sense of self and merging with infinity by floating in a pitch black tank filled with water and Epsom salts on acid with American scientist John C. Lilly. Let's dive in.

The universe is on my mind. On 2 August 2022, I was invited to Breckland Astronomical Observatory to interview Dan Self, a scientist obsessed with the skies. Beneath a streak of Milky Way so fresh it looked pixelated, we peered through a 20-inch aperture at Saturn and its rings, Jupiter and its moons. We stepped back from the telescope and scanned the firmament for the Andromeda Galaxy – looking back through 2.5 million lightyears of chaotic time at the furthest thing perceptible by the naked eye.

From the observatory's brainlike dome I stared out at the uncomprehending darkness bursting with pockets of light — a "night sky with exit wounds", in poet Ocean Vuong's words. I felt simultaneously large and small, consequential and incidental, affinitive and alien.

I recognised this state of mind. I had inhabited it during a recent trip to Float Norwich where I spent an hour in a sensory deprivation tank. In the pod, the body floats supine in a solution of water and magnesium sulphate. It is a total blackout — no people, no light, no acoustics, no gravity.

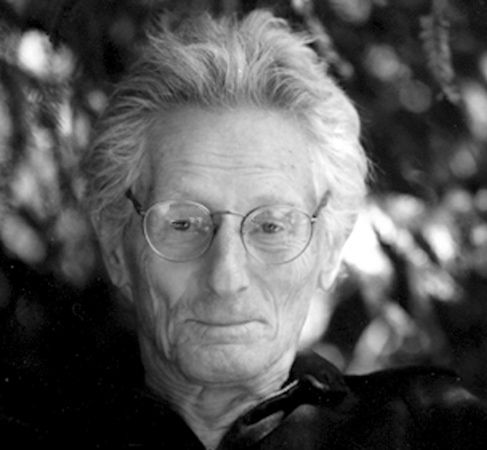

The isolation tank was invented in 1954 by John C. Lilly — a controversial and pioneering scientist and psychoanalyst. Lilly became a critical figure in a generation of countercultural thinkers, influencing Timothy Leary, Ram Dass and Arthur C. Clarke. The film Altered States (1980) is inspired by Lilly.

He sought to create an environment that attenuated 99% of all sensory stimulus input — "a black hole in psychophysical space; psychological free-fall". His book The Deep Self recounts Lilly's experiments with LSD and meditation in the isolation chamber and his attempts to expand the frontiers of consciousness.

Lilly calls the sensory deprivation tank a "liquid interface", a "roomy lotuslike container", a "real, live experiential mandala" capable of producing some "uniquely cosmic experiences".

Lilly would take acid, step into the pod and psychedeliquesce.

"I realised, finally, that the depths of mind are as great as the depths of cosmic outer space. There are inner universes as well as outer ones."

This is an idea we encountered in the last edition of Afterglow when discussing Stanislav Grof and LSD therapy. Lilly wisely acknowledges that a revelation of this kind can be psychologically perilous, as an encounter with infinity can efface our stable sense of self and undermine our sense of reality. But he also underlines how it can be transcendental.

"Realisation of the lack of any limits in the mind is not easy to acquire. The domains of direct experience of infinities within greater infinities of experience are sometimes frightening, sometimes 'awe-full', sometimes 'bliss-full'."

To cope with the overwhelming immensity of the mind, of infinity, of outer space, we must get in touch with what Lilly calls the "simplest truth" — just being, not doing.

"To arrive at the simplest truth, as Newton knew and practised, requires years of contemplation. Not activity. Not reasoning. Not calculating. Not busy behaviour of any kind. Not reading. Not talking. Not making an effort. Not thinking. Simply bearing in mind what it is one needs to know."

If you cannot afford to pay for a sensory deprivation session, there are other ways of achieving this. One method is dopamine fasting, which I have experimented with before and plan to write about in the future. Other avenues include psychedelic experiences, meditation or even stargazing — whatever disarms your urge to action and induces a state of simply existing.

In The Power of Myth, American academic Joseph Campbell talks about the necessity to establish your own "bliss station".

"You must have a room, or a certain hour or so a day, where you don’t know what was in the newspapers that morning, you don’t know who your friends are, you don’t know what you owe anybody, you don’t know what anybody owes to you. This is a place where you can simply experience and bring forth what you are and what you might be. This is the place of creative incubation. At first you may find that nothing happens there. But if you have a sacred place and use it, something eventually will happen."

We will examine how Campbell's work on mythology can be applied to the psychedelic experience in next week's Afterglow newsletter.

Until then, try doing nothing.

Charles Bliss

What is total #sensorydeprivation like?

— Charles Bliss (@thecharlesbliss) July 7, 2022

This was my experience of floating in an isolation tank: https://t.co/fB6Ab6eKFi

🤯 Mind at Large

A breakdown of mind-blowing ideas I encountered this week:

📖 Book – If you're into being instead of doing, you might enjoy The Power of Now by Eckhart Tolle, which attempts to dismantle the concepts of past and future to become fluid in the present moment.

🎬 Video – Chemist and journalist Hamilton Morris made a splashinating three-part documentary on sensory deprivation tanks and John C. Lilly. Check it out below.

"The most valuable thing we can do for the psyche, occasionally, is to let it rest, wander, live in the changing light of a room, not try to be or do anything whatever."

May Sarton

🫠 Enjoying this newsletter?

Forward to a friend and let them know where they can subscribe.